"As I am speaking of poetry, it will not be amiss to touch slightly upon the most singular heresy in its modern history-the heresy of what is called, very foolishly, the Lake School. "I dare say Milton preferred 'Comus' to either. But, in fact, the 'Paradise Regained' is little, if at all, inferior to the 'Paradise Lost,' and is only supposed so to be because men do not like epics, whatever they may say to the contrary, and, reading those of Milton in their natural order, are too much wearied with the first to derive any pleasure from the second. By what trivial circumstances men are often led to assert what they do not really believe! Perhaps an inadvertent word has descended to posterity. There are, of course, many objections to what I say: Milton is a great example of the contrary but his opinion with respect to the 'Paradise Regained' is by no means fairly ascertained. Therefore a bad poet would, I grant, make a false critique, and his self-love would infallibly bias his little judgment in his favor but a poet, who is indeed a poet, could not, I think, fail of making-a just critique whatever should be deducted on the score of self-love might be replaced on account of his intimate acquaintance with the subject in short, we have more instances of false criticism than of just where one's own writings are the test, simply because we have more bad poets than good. I remarked before that in proportion to the poetical talent would be the justice of a critique upon poetry. I think the notion that no poet can form a correct estimate of his own writings is another.

"I mentioned just now a vulgar error as regards criticism. Our antiquaries abandon time for distance our very fops glance from the binding to the bottom of the title-page, where the mystic characters which spell London, Paris, or Genoa, are precisely so many letters of recommendation. Besides, one might suppose that books, like their authors, improve by travel-their having crossed the sea is, with us, so great a distinction. I say established for it is with literature as with law or empire-an established name is an estate in tenure, or a throne in possession. He is read, if at all, in preference to the combined and established wit of the world. "You are aware of the great barrier in the path of an American writer. This neighbor's own opinion has, in like manner, been adopted from one above him, and so, ascendingly, to a few gifted individuals who kneel around the summit, beholding, face to face, the master spirit who stands upon the pinnacle. But the fool's neighbor, who is a step higher on the Andes of the mind, whose head (that is to say, his more exalted thought) is too far above the fool to be seen or understood, but whose feet (by which I mean his everyday actions) are sufficiently near to be discerned, and by means of which that superiority is ascertained, which but for them would never have been discovered-this neighbor asserts that Shakespeare is a great poet-the fool believes him, and it is henceforward his opinion. A fool, for example, thinks Shakespeare a great poet-yet the fool has never read Shakespeare. It appears then that the world judge correctly, why should you be ashamed of their favorable judgment?' The difficulty lies in the interpretation of the word 'judgment' or 'opinion.' The opinion is the world's, truly, but it may be called theirs as a man would call a book his, having bought it he did not write the book, but it is his they did not originate the opinion, but it is theirs. Another than yourself might here observe, 'Shakespeare is in possession of the world's good opinion, and yet Shakespeare is the greatest of poets. On this account, and because there are but few B-'s in the world, I would be as much ashamed of the world's good opinion as proud of your own. This, according to your idea and mine of poetry, I feel to be false-the less poetical the critic, the less just the critique, and the converse. "It has been said that a good critique on a poem may be written by one who is no poet himself. Nor have I hesitated to insert from the 'Minor Poems,' now omitted, whole lines, and even passages, to the end that being placed in a fairer light, and the trash shaken from them in which they were imbedded, they may have some chance of being seen by posterity. I have therefore herein combined 'Al Aaraaf' and 'Tamerlane' with other poems hitherto unprinted. Believing only a portion of my former volume to be worthy a second edition-that small portion I thought it as well to include in the present book as to republish by itself.

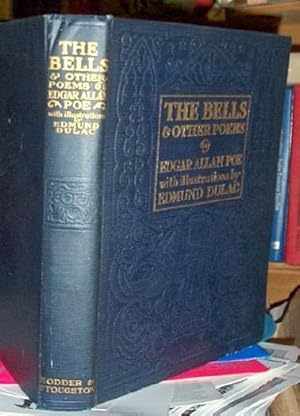

EDGAR ALLAN POE THE BELLS TRASH IT UPDATE

You should visit Browse Happy and update your internet browser today! The embedded audio player requires a modern internet browser.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)